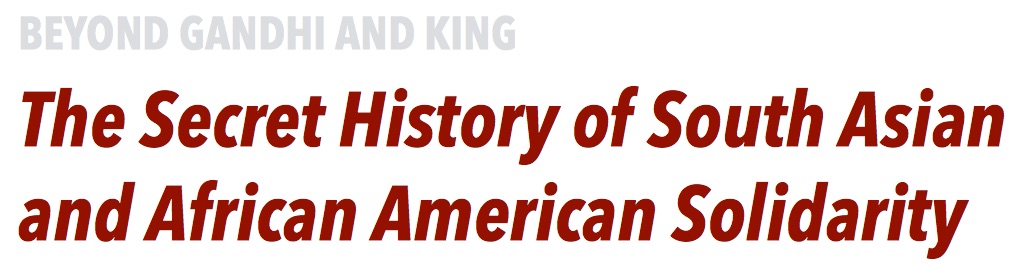

In 1942, the Black press was heavily covering the widespread anti-colonial civil disobedience in India. Writes Nico Slate in Colored Cosmopolitanism:

While most American newspapers closely covered the outbreak of civil disobedience in India, it was the African American press that recognized the racial framework in which Gandhi, Nehru, and other leading Indian figures positioned their struggle. Black interest in India had risen dramatically during the noncooperation and civil disobedience movements, and it peaked again in the wake of the Quit India declaration. On September 26, over eighty Black intellectuals sent President Roosevelt a joint letter encouraging him to take decisive action to resolve the crisis in India. That same day, sociologist and Pittsburgh Courier columnist Horace Cayton told readers of The Nation “it may seem odd to hear India discussed in pool rooms in South State Street in Chicago, but India and the possibility of the Indians obtaining their freedom from England by any means has captured the imagination of the American Negro.” In October the Courier publish the results of a poll in which 87.8% of ten thousand black respondents answered yes to the question, “Do you believe that India should contend for her rights and her liberty now?”

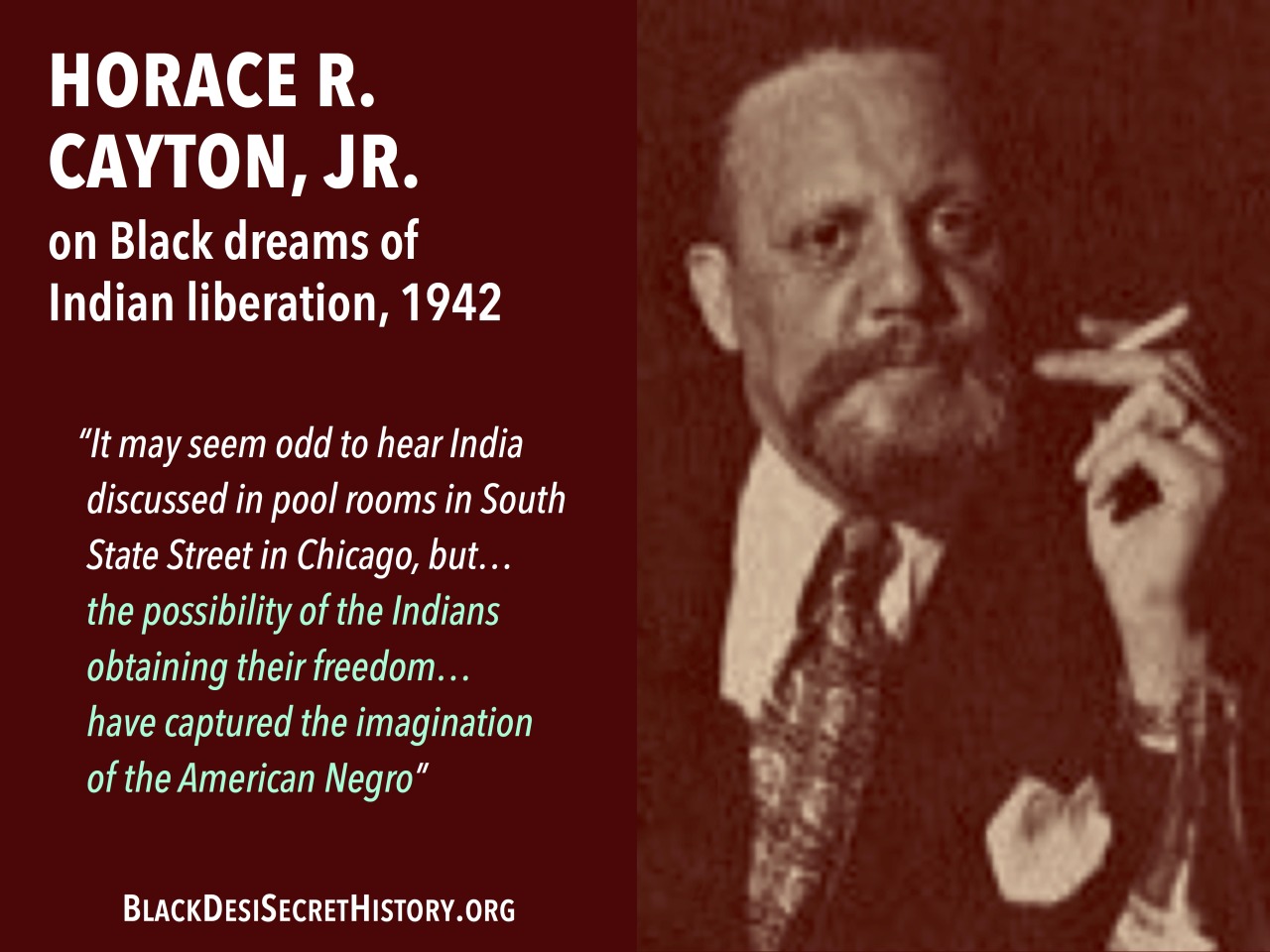

Bayard Rustin was an American civil rights, gay rights, and nonviolence activist and icon, perhaps best known as the lead organizer of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

In 1945, while in prison for being a pacifist, Rustin organized the Fellowship of Reconciliation’s Free India Committee, which stood on the side of India against the British empire.

In 1949, according to Daniel Levine’s Bayard Rustin and the Civil Rights Movement, Rustin visited India to attend a planned conference on pacifism at Santiniketan near Calcutta organized by Gandhi. Gandhi was assassinated, and conference fundraising fell through, but Rustin spent seven weeks in India and Pakistan, learning Gandhian nonviolent civil resistance techniques which he could call on over the course of his activism.

John D’Emilio’s Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin describes Rustin’s engagement with South Asia, starting with his 1949 visit, where he met everyone from Prime Minister Nehru to Dalit community members, visiting Bombay, Mysore, Delhi, Jaipur, and Lahore. He helped plan Martin Luther King, Jr.’s 1959 visit to India, and returned to India again in 1960, attending the War Resisters International conference, and traveling with Vinoba Bhave. He returned to Pakistan in 1982, visiting Afghan refugees.

Photo credit: Warren K. Leffler, 1963

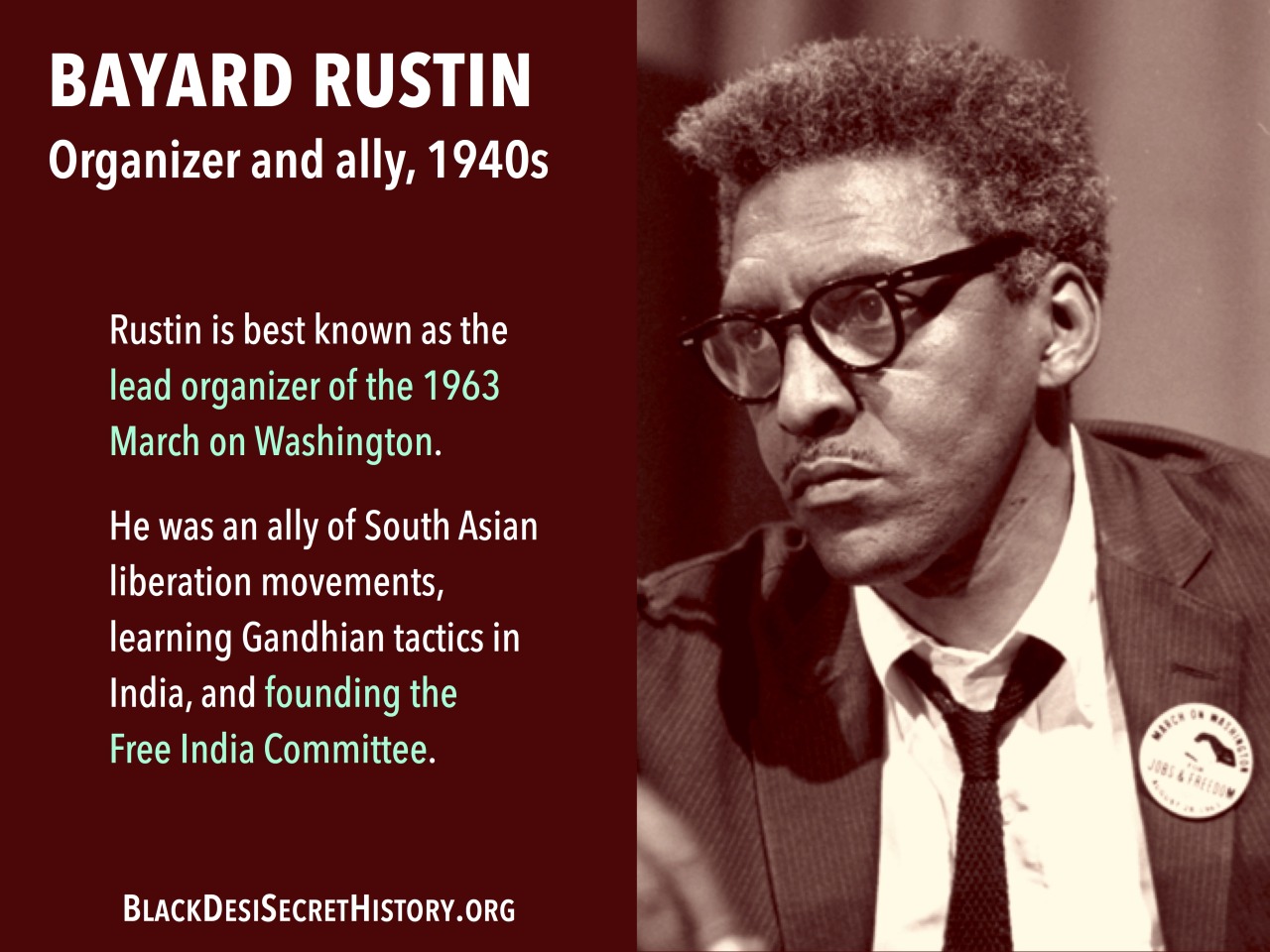

Historian Vivek Bald has been working on Lost Histories of South Asian America — a project to recover the stories of two waves of primarily Bengali Muslim men who came to the United States between the 1880s and 1940s, many of whom married and built new lives with African American, Creole, and Puerto Rican partners.

The stories are told through a popular and accessible book, a website, and an upcoming documentary.

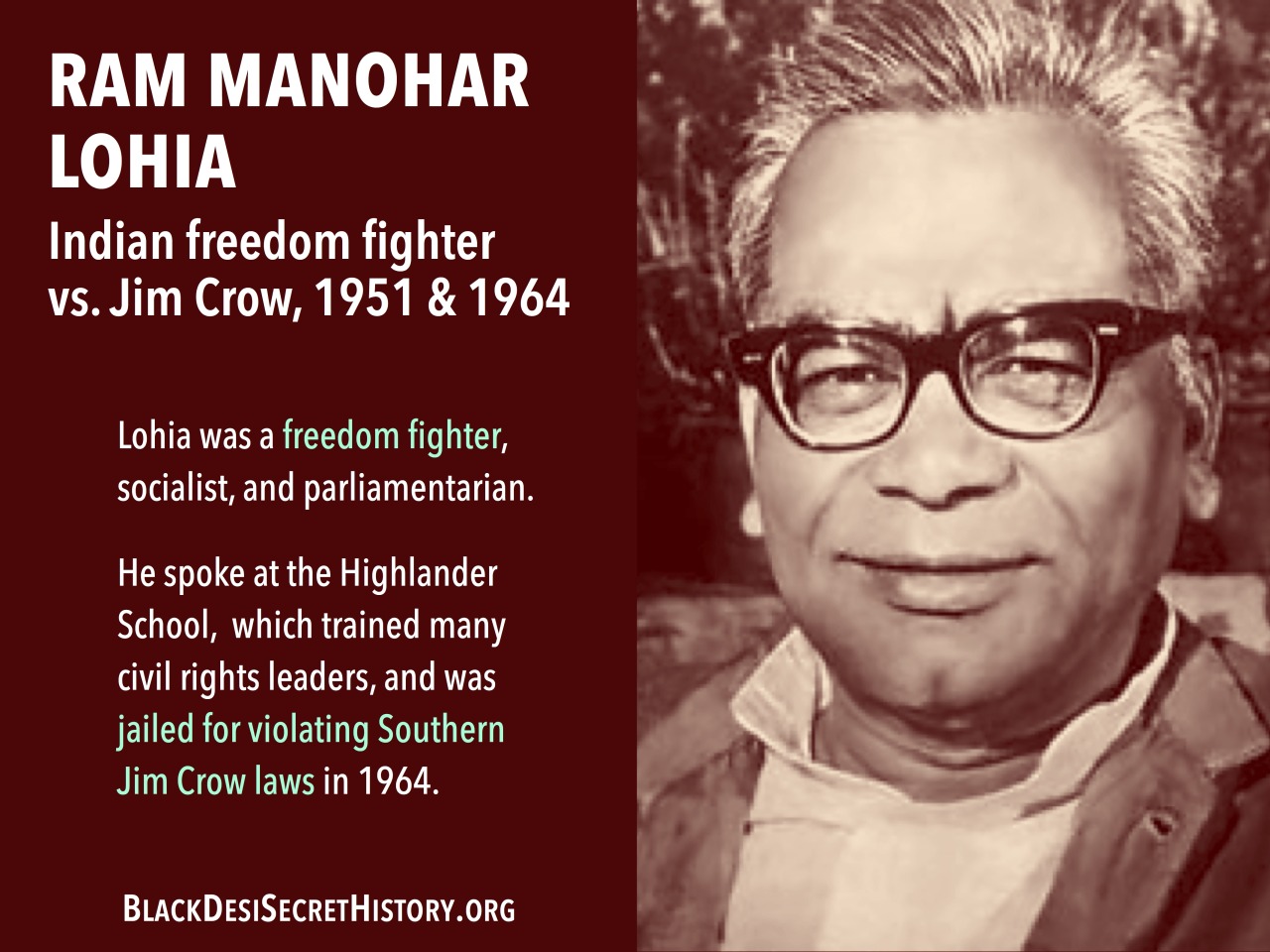

Ram Manohar Lohia was an Indian freedom fighter and member of parliament who went to jail to fight Jim Crow.

In 1951, he lectured at Fisk University and at the Highlander Folk School activist training center, encouraging African Americans to use nonviolent civil disobedience.

Nico Slate describes Lohia’s 1964 return to the U.S. in Colored Cosmopolitanism:

On May 28, 1964, more than a decade after he had traveled through the American encouraging African-Americans to embrace Gandhian civil disobedience, Rammanohar Lohia, now a prominent member of the Indian Parliament, himself offered satyagraha in Jackson, Mississippi. Lohia relished the opportunity to be arrested for confronting Jim Crow. He had been turned away from Morrison cafeteria the night before his arrest and chose to return in order to court arrest. In dressed in sparkling-white clothes that distinguished him as Indian, Lohia attempted to enter the restaurant for the second time…The police arrested him, put him in a paddy wagon, and drove him away from the restaurant before releasing him. The State Department promptly sent a formal apology to the Indian ambassador. Decrying his treatment as “tyranny against the United States Constitution,” Lohia told reporters that both the State Department and the Indian Embassy “may go to hell.” Segregation was a moral issue, he stressed, not a political one. When told that the American ambassador to the United Nations…would offer his apologies, Lohia replied that Stevenson should apologize to the State of Liberty.

African American activists helped created South Asian America as we know it.

South Asian America was built on the backs of Black bodies during the Civil Rights movement, which helped force the end of racist immigration laws that limited immigration from South Asian nations to just 100 people per year.

The change in the laws was driven by at least four factors: racist immigration laws being seen as embarassing (1) domestically during the Civil Rights Movement and (2) internationally in the Global South during the Cold War, (3) the need for high-skills labor, and (4) pressure from Irish, Italian, and Greek immigrant communities in support of family reunification.

Our right to exist with dignity in the United States wasn’t just handed to us — it was won for us in no small part by communities of color and anti-racist activists. (Read Vijay Prashad’s The Karma of Brown Folk for a clear explanation of South Asian immigration and American race politics.)

In the wake of Ferguson, South Asians across the United States have been speaking out, taking action, and deepening conversations for Black lives and power:

- Sasha W: The Revolution Starts with My Thathi: Strategies for South Asians to Bring #BlackLivesMatter Home

- QSANN: A Week of Queer South Asian Rage

- Jaya Sundaresh: South Asians and Ferguson: #StartTheConversation

- Deepa Iyer: Dispatch from Ferguson: Convenience Store Owners Talk Race

- Vijay Prashad: Black Bodies, Broken Worlds

- Taz Ahmed: Love in Protest

- Mai Bhago: Especially in the Wake of Ferguson, It’s Time to Destroy Anti-Blackness in the Sikh Community

- DRUM: Notes from a community speakout

- Nadia Khastagir: Our Name is Rebel: #Asians4BlackLives Protest Police Violence

- Anita Felicelli: What Ferguson Teaches Us About America’s Caste System

- Jaya Sundaresh: Why Ferguson Matters: Desi Tweet Round-Up

- Quartz India: America’s police brutality protests have now reached New Delhi

Photo credit: Simmy Makhijani

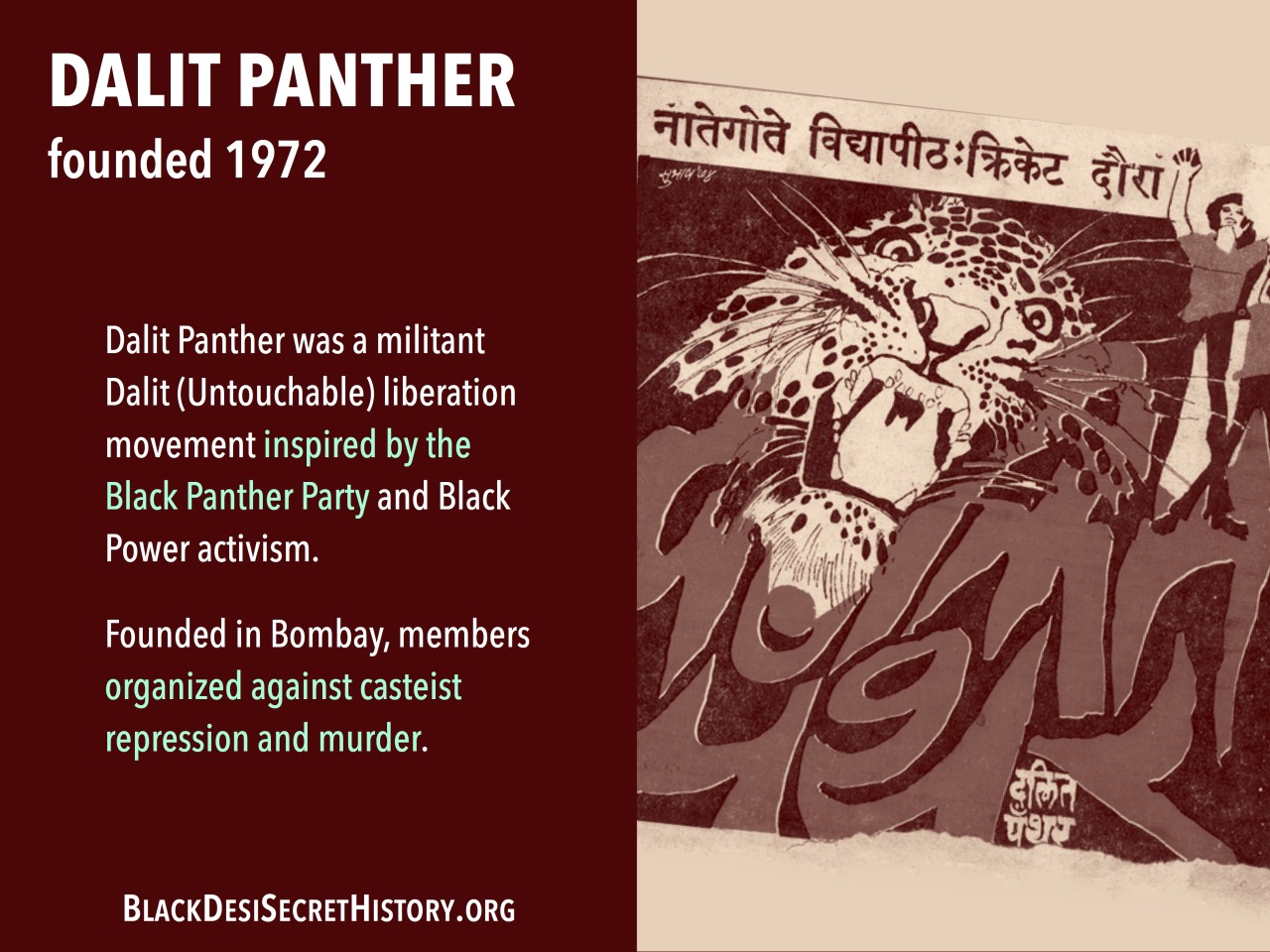

Dalit Panther linked Black Power and Dalit organizing. According to Dalits and Human Rights (ed. Prem Kumar Shinde):

The Dalit Panthers were formed in the state of Maharashtra in the 1970s, ideologically aligning themselves to the Black Panther movement in the United States. During the same period, Dalit literature, painting, and theater challenged the very premise and nature of established art forms and their depiction of society and religion. Many of these new Dalit artists formed the first generation of the Dalit Panther movement that sought to wage an organized struggle against the varna system. Dalit Panthers visited “atrocity” sites, organized marches and rallies in villages, and raised slogans of direct militant action against their upper-caste aggressors.

Conversely, Dalits have sometimes been framed as “Black Untouchables” by African American internationalists — an act of solidarity through an imagined racial connection.

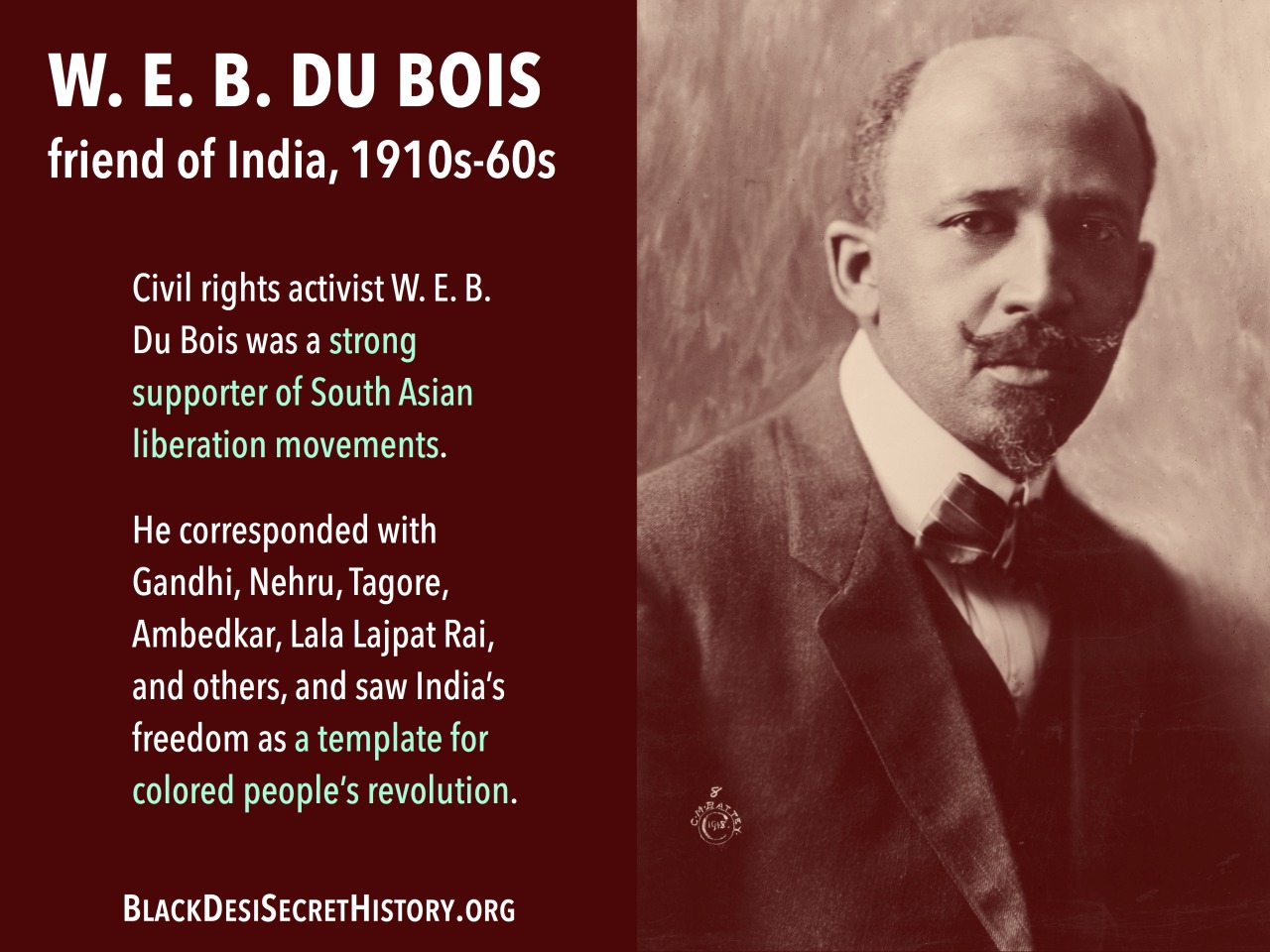

W. E. B. DuBois was probably the central African American ally to South Asian liberation movements. While much has been written about the relationship, I recommend Raising Up a Prophet and Colored Cosmopolitanism.

Photo credit: Cornelius M. Battey, 1918

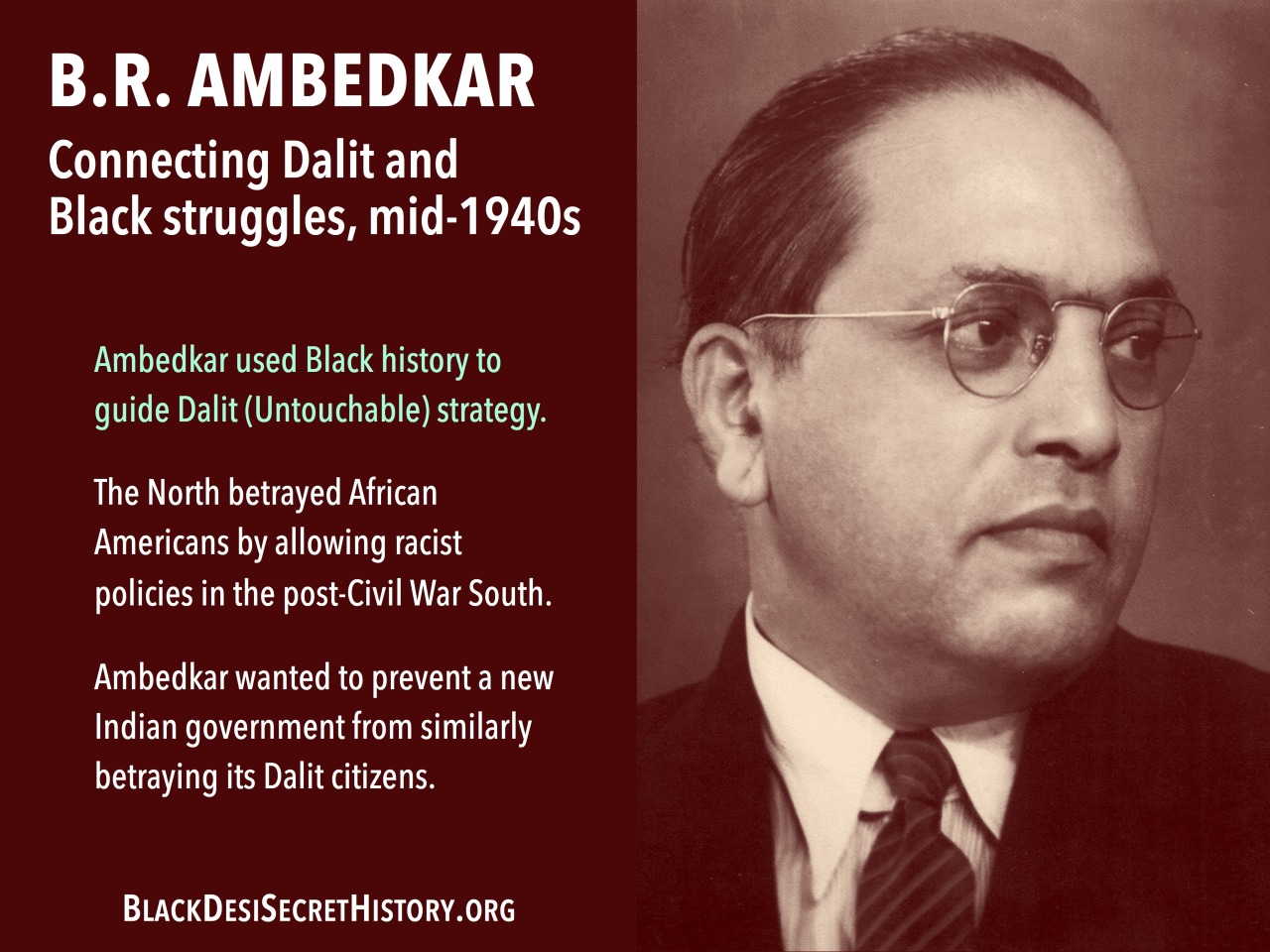

B.R. Ambedkar was the chief architect of the Indian Constitution and the best-known Dalit (Untouchable) civil rights activist of the 20th century.

In Colored Cosmopolitanism, Nico Slate describes how Ambedkar used the example of African American struggles to guide him in his thinking. In What Congress and Gandhi Have Done to the Untouchables he “wrote three pages on on Northern betrayal of African Americans after the Civil War, comparing Gandhi and the Congress Party to the North, and concluding “The Untouchables cannot forget the fate of the Negroes. It is to prevent such treachery that the Untouchables have taken the attitude they have with regard to this ‘Fight for Freedom.’”

The South Asian American Digital Archive’s blog describes Ambedkar’s attempt to connect with W. E. B. Du Bois:

“In the 1940s, Ambedkar contacted Du Bois to inquire about the National Negro Congress petition to the U.N., which attempted to secure minority rights through the U.N. council. Ambedkar explained that he had been a “student of the Negro problem,” and that “[t]here is so much similarity between the position of the Untouchables in India and of the position of the Negroes in America that the study of the latter is not only natural but necessary.” Du Bois responded by telling Ambedkar he was familiar with his name, and that he had “every sympathy with the Untouchables of India.”

Photo credit: Unknown, 1939

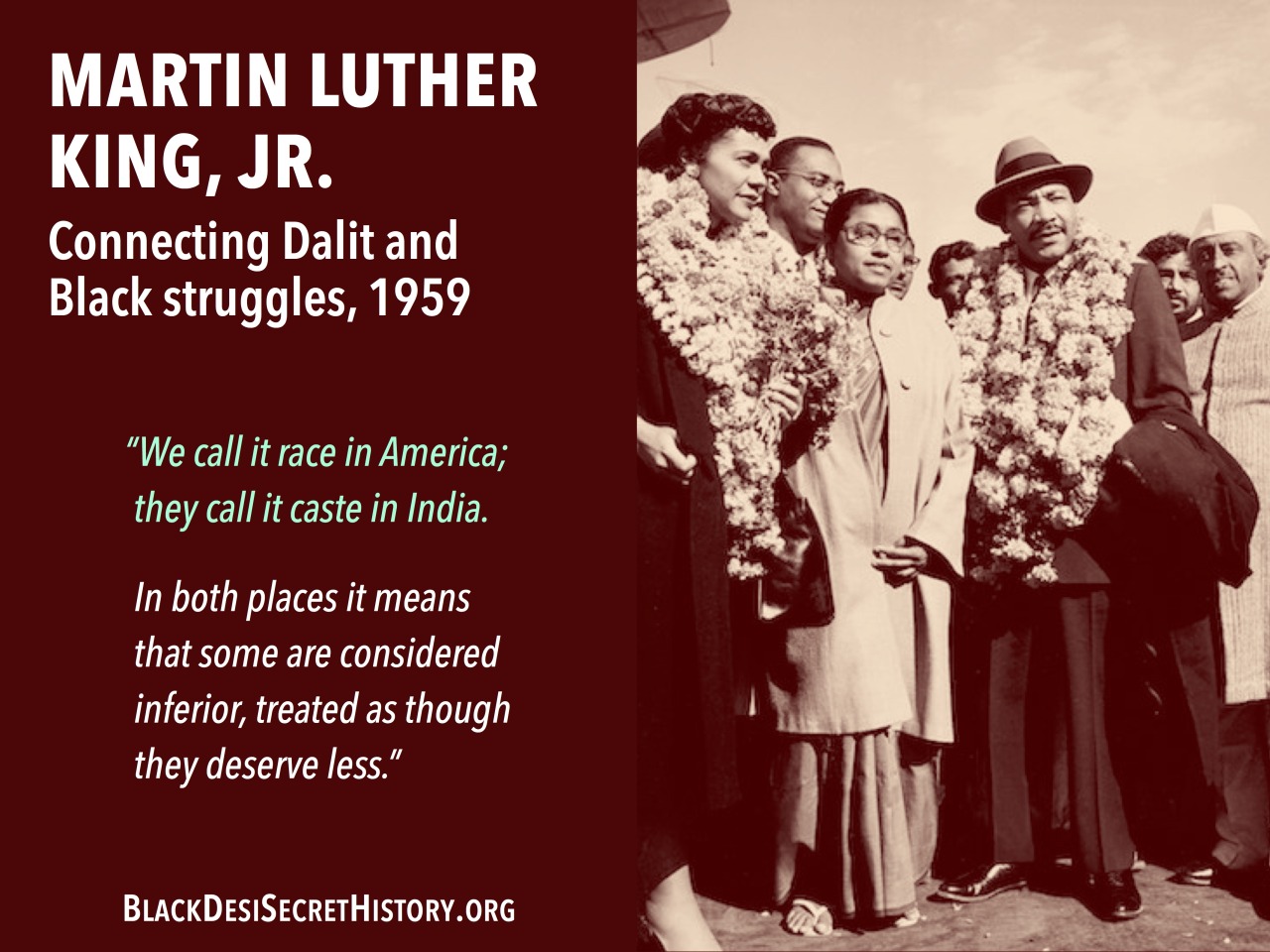

Martin Luther King, Jr. traveled to India in 1959. He wrote about his trip in an article titled “My Trip to the Land of Gandhi,” where he lauds India’s progress against caste oppression. Half a century on, it’s obvious that King was viewing Indian anti-caste policy through intensely rose-colored glasses, but the strategic utility of using India to shame the American government is evident:

We were surprised and delighted to see that India has made greater progress in the fight against caste “untouchability” than we have made here in our own country against race segregation. Both nations have federal laws against discrimination (acknowledging, of course, that the decision of our Supreme Court is the law of our land). But after this has been said, we must recognize that there are great differences between what India has done and what we have done on a problem that is very similar. The leaders of India have placed their moral power behind their law. From the Prime Minister down to the village councilmen, everybody declares publicly that untouchability is wrong. But in the United States some of our highest officials decline to render a moral judgment on segregation and some from the South publicly boast of their determination to maintain segregation. This would be unthinkable in India.

Moreover, Gandhi not only spoke against the caste system but he acted against it. He took “untouchables” by the hand and led them into the temples from which they had been excluded. To equal that, President Eisenhower would take a Negro child by the hand and lead her into Central High School in Little Rock.

King wasn't the only one analogizing caste and race. Equality Labs' Caste in the United States report describes how early "upper" caste immigrants like Bhagat Singh Thind made the same argument, telling courts that caste privilege was akin to Whiteness.

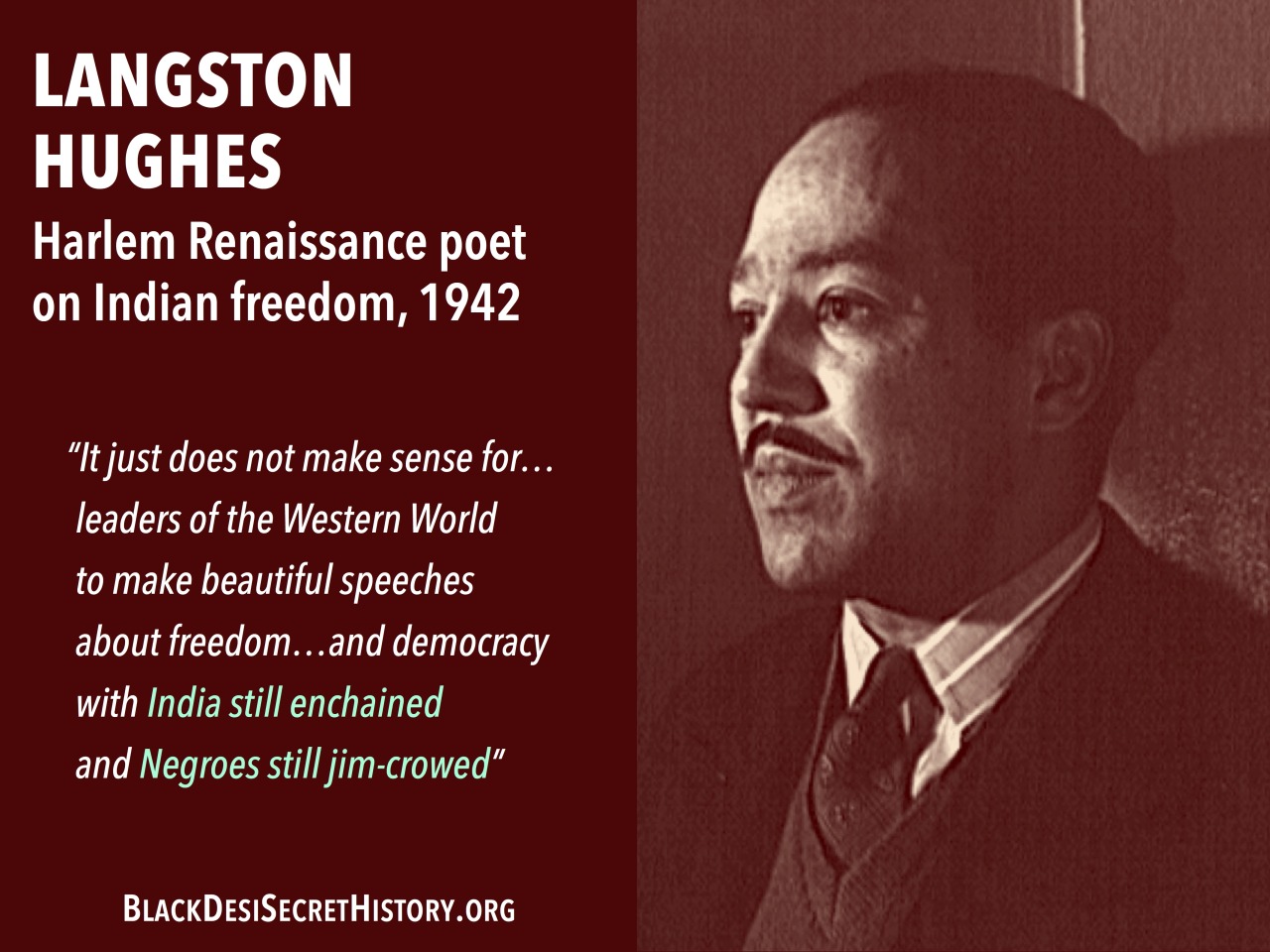

Langston Hughes wrote often in support of freedom for India. His poems referencing the Indian freedom struggle include “How About It?,” “Jim Crow’s Last Stand,” “Ghandi [sic] is Fasting,” “Merry Christmas,” “Explain It, Please,” “Freedom [2],” “Scottsboro,” and “Goodbye Christ.”

An excerpt from “How About It?”:

Show me that you mean

Democracy please—

Cause from Bombay to Georgia

I’m beat to my knees

You can’t lock up Nehru

Club Roland Hayes,

Then make fine speeches

About Freedom’s way.

Photo credit: Jack Delano

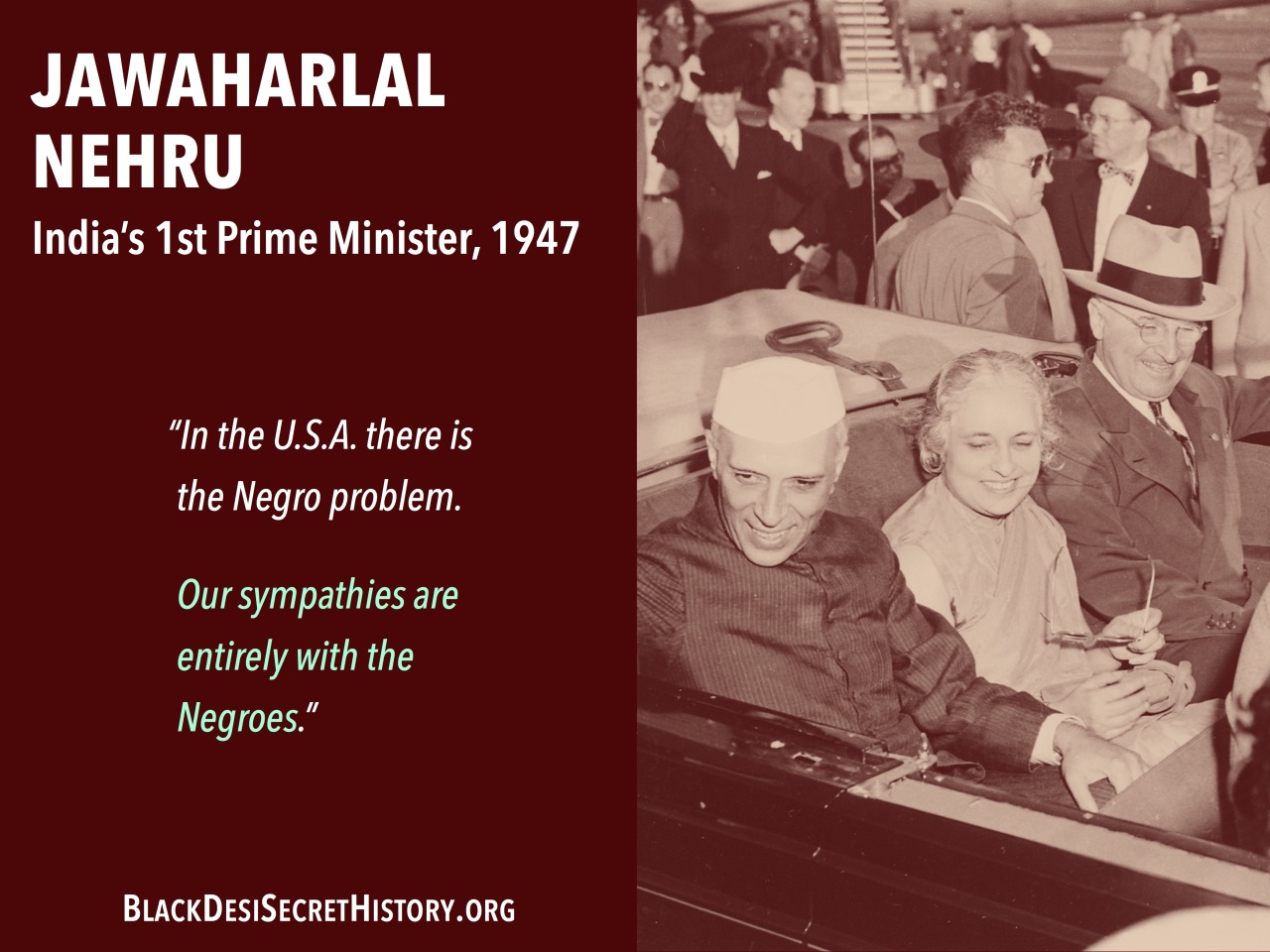

Jawaharlal Nehru, anti-colonial leader and first Prime Minister of India, was a strong supporter of African American left activists, both directly through friends like Paul Robeson and through intermediaries like Cedric Grover. But, as Nico Slate describes in Colored Cosmopolitanism, "Indian independence transformed Nehru from an anticolonial freedom fighter to the leader of a nation-state. The need to maintain cordial relations with the United States strained his solidarity with Black Struggles.“ In a secret memo to the first Indian ambassadors to the US and China, Nehru was frank about how "Our sympathies are entirely with the Negroes,” even as his new government struggled to handle the white American government as it approached the height of its post-Cold War power.

Photo credit: Abbie Rowe, “Photograph of President Truman, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, and Nehru’s sister, Madame Pandit,” 1959

Freedom fighter and arts advocate Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay connected with African American activists while she was in the United States. Writes Nico Slate in Colored Cosmopolitanism:

For Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, one of the most articulate champions of colored cosmopolitanism, being a woman, being socialist, and being “colored” were all vital to her identity and her sense of purpose. Her nearly two years in the United States allowed her to reach out to African Americans as a “coloured woman” who had dedicated her life to opposing not only imperialism and racism but gender-based oppression as well.

While traveling through the South, Chattopadhyay “made a point of staying only with African American families”; these acts of solidarity and the support she received from African American communities and leaders were reported on in Indian newspapers.

James Lawson was a theoretician of nonviolence during the Civil Rights Movement and beyond.

He first encountered Gandhi through the Black press: “I probably first met Gandhi in the pages of black newspapers in our home. I didn’t really read a book by Gandhi until 1947, my first year of college. A lot of black newspapers saw Gandhi as an ally in the struggle against racism and Jim Crow and American apartheid. They thought what he was doing in India and South Africa were of utmost importance for black people to know about.”

Lawson spent three years as a Methodist missionary, working as a teacher and campus minister at Hislop College in Nagpur, Maharashtra, where he studied satyagraha from Gandhi’s disciples. When he returned to the U.S., Lawson became a key nonviolent organizer in Nashville and elsewhere throughout the South.

Photo credit: Mug shot from arrest in Jackson, Mississippi, May 24, 1961

K.A. Abbas was an Indian director and prolific writer. He wrote about his time in the U.S. in a now hard-to-find 1943 book called An Indian Looks at America.

According to Nico Slate in Colored Cosmopolitanism, “Abbas combined his critique of American racism with an awareness of class inequalities. He argued that communists were relatively free of racial discrimination, criticized northern capitalists for exploiting African-Americans, and compared the ‘colored bourgeois’ to the 'Indian capitalists who saw in nationalism a means of their economic gains.’”

Abbas attended the World Youth Congress in New York, where he attended a reception given by the Ethiopian World Federation. Abbas was put off by a speaker who “invited us to join a colored world front against all White people and said we should do the white races exactly what they had done to us.” Writes Slate:

Abbas began by…assuring the American Negroes that we were with them in their struggle for the attainment of complete political, social and economic equality in the country.“ He told the audience, however, that global oppression was "not a question of color at all” but of the “historical inter-relation between imperialism, militarism, capitalism, and fascism.” Abbas directed the audience to examine the root causes of racism rather than the division between white and “colored” peoples.

Photo credit: Unknown (“Young Abbas in Bombay” via the K.A. Abbas Memorial Trust)

In Colored Cosmopolitanism, Nico Slate writes on Mary McLeod Bethune’s "strong ties" to Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit through the mid-1940s and early 1950s. She was also part of a small group of African American activists who met Jawaharlal Nehru in New York in 1949.

Photo credit: Carl Van Vechten, 1949

The Anagarika Dharmapala spoke on Buddhism at the 1893 World Conference on Religions in Chicago. On a subsequent trip, he met African American educator Booker T. Washington in San Jose, California, heard him speak in San Francisco, and eventually went to visit his Tuskegee Institute, which he praised in this lovely letter to Booker T. Washington:

I have gained from my visit to Tuskegee an experience and when I saw the Tuskegee Institute with its manifold branches under enlightened teachers I rejoiced that you have made all this glorious work a consummation within a generation; and I thought of the Viceroy in India who with the millions of children starving for education and bread that he should waste in sky rockets and tomfoolery and vain show to please a few loafing lords who came from England last January six million dollars in thirteen days! He is not worth to loose the latchet of your shoe.

Photo credit: Unknown, 1893

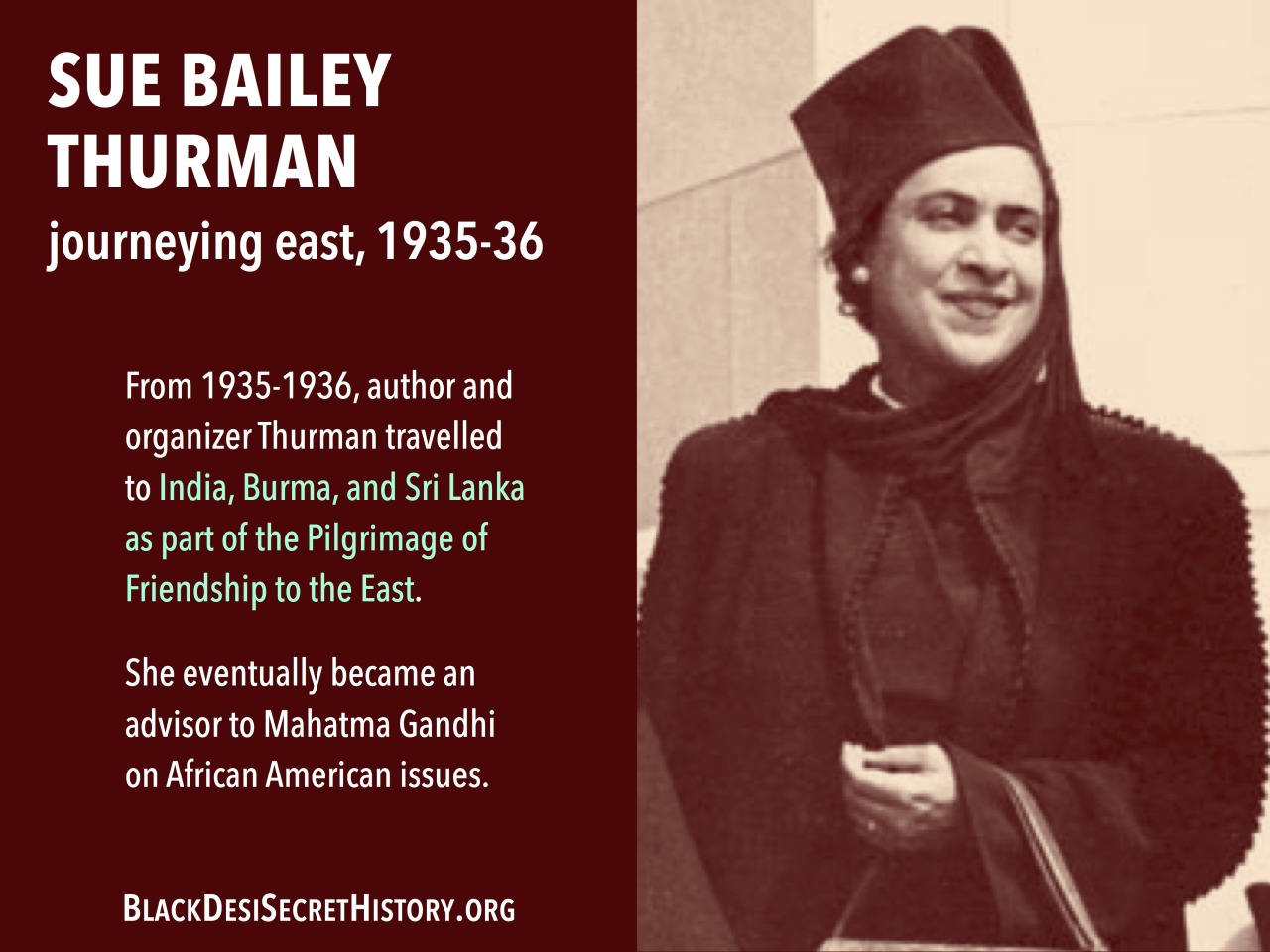

Sue Bailey Thurman was a writer, activist, and cultural worker, along with her husband theologian and activist Howard Thurman. Her global vision connected her to South Asia and many other parts of the world.

Photo credit: Unknown, taken in 1953

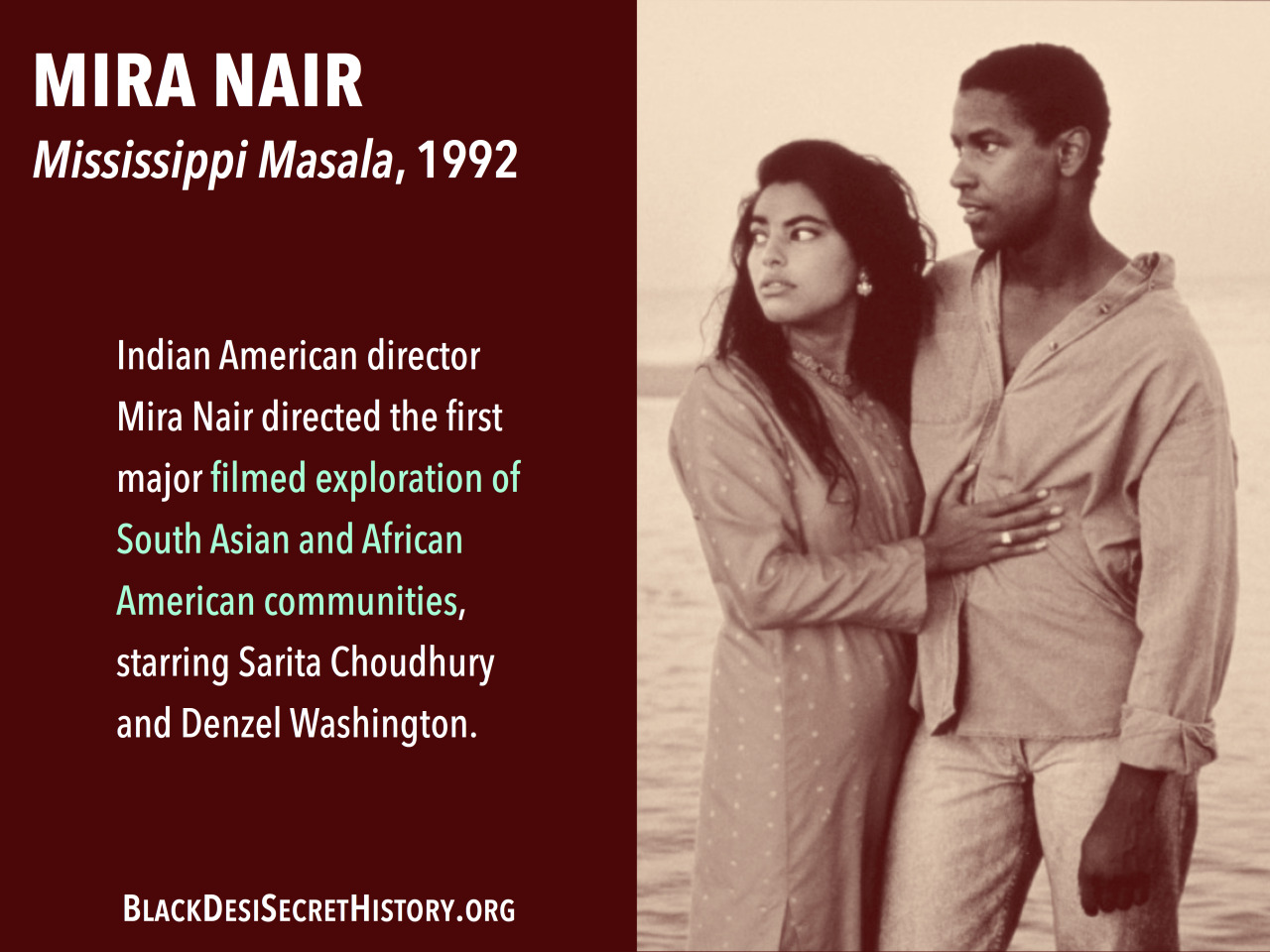

When the South Asian American community was still (relatively) small, Mira Nair’s Mississippi Masala publicly broke generations of silences about Black and Desi lives, telling a story weaving through India, Uganda, and Mississippi. Like the stories unearthed by Vivek Bald, Nair's film reminds us that our solidarity histories include bonds of intimate solidarity.

![ANAGARIKA DHARMAPALA, Sri Lankan Buddhist scholar writing to Booker T. Washington, 1903: “I have gained from my visit to Tuskegee an experience that I shall never forget…[I] thought of the Viceroy in India who…is not worth to loose the latchet of your shoe.”](img/history/anagarika-dharmapala.jpg)